Vietnam, Algeria, Palestine: Passing on the torch of the anti-colonial struggle

by Hamza Hamouchene Originally published at: https://www.tni.org/en/article/vietnam-algeria-palestine Introduction ‘Revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; […]

Webinar on The Geopolitics of Green Colonialism: Global Justice and Ecosocial Transitions

As the ecological and climate crisis deepens, the Global North has put forward (false) solutions such as renewable energy, electric cars, carbon trading, and green […]

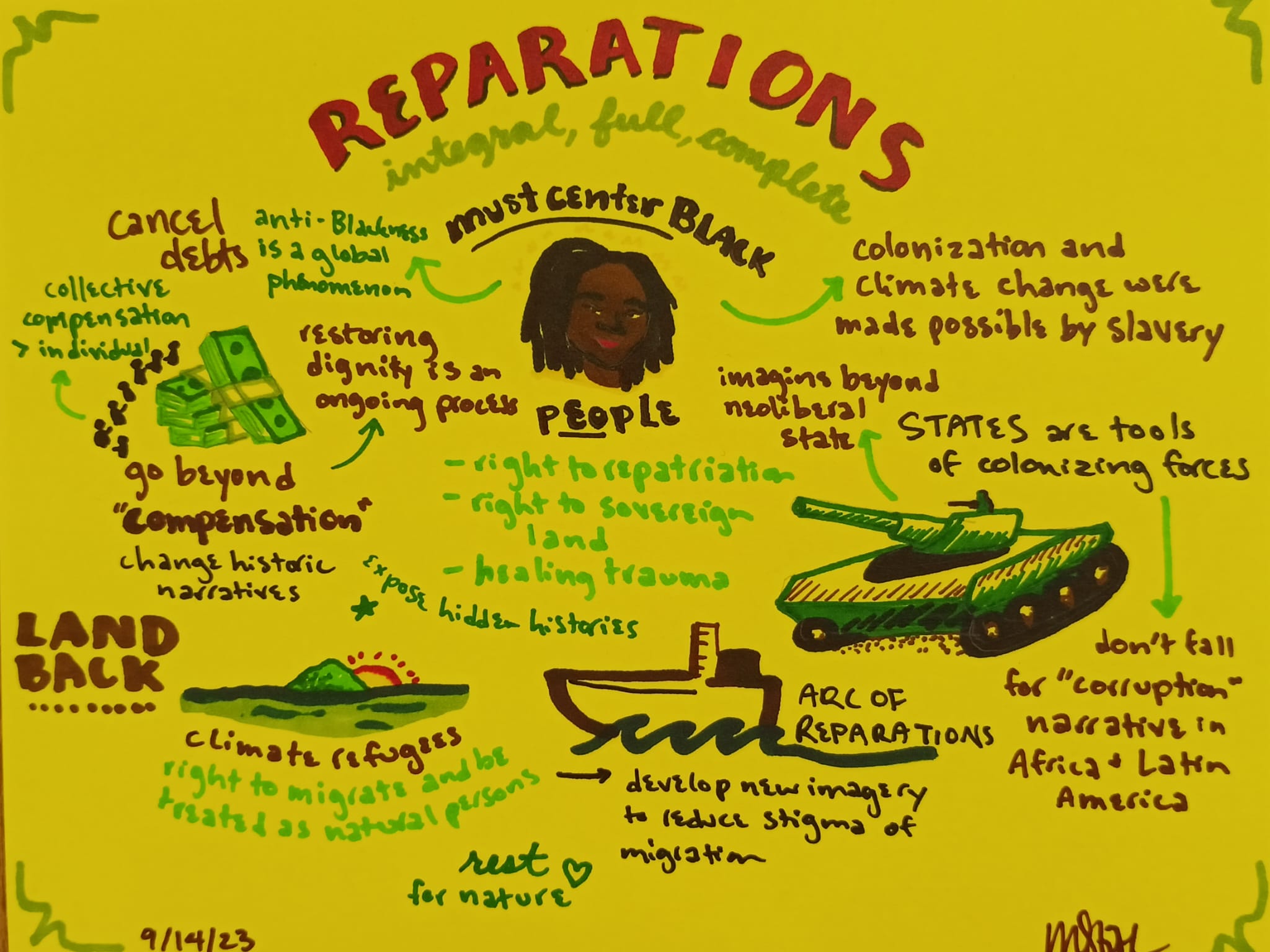

[2023] Debts and Reparations (Jackson)

We are daughters for freedom, we are cimarronas, we are the Mississippi, the Cauca, the Magdalena, the Atrato… we are happy and rebellious caribbeans, we […]