by Miriam Lang

With COP16 underway in Cali, Colombia, Miriam Lang highlights the risk of focusing on biodiversity credits as a solution to preserving biodiversity may preclude discussions of a transformative politics outside of a market-based logic. What is needed is a change of the very logic that drives environmental politics at all levels towards one that foregrounds relational worldviews, care and reciprocity with nature instead of the patriarchal, modern impulse to commodify, dominate, and destroy it.

From October 21 to November 1, the sixteenth Conference of the Parties (COP) on

biodiversity will take place in Cali, Colombia. The COP is the governing body of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), an international treaty adopted at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. The Colombian government titled this edition of the biannual event “The COP of the people and reconciliation.” The official slogan “Peace with Nature” invites us to “rethink an economic model that does not prioritize the extraction, overexploitation and pollution of nature.” A heated dispute is announced between a concerned and mobilized civil society, in which, in addition to the environmentalist movement, indigenous peoples and their organizations stand out; a host government that has declared the country a “world power of life” and at least discursively, has shown itself to be the most pro-environmental Latin American government; and, finally, a multilateral process that has already opened the doors in a big way to companies, banks and investment funds. These actors hope that biodiversity credits – analogous to carbon credits – that can be traded internationally to supposedly compensate for biodiversity loss will be standardized. But what are the implications and consequences of this conversion of the fabric of life itself into a commodity?

When it comes to protecting life, no sacrifice, no cost can be exaggerated. Strangely, when it comes to protecting the fabric that makes life possible, that complex planetary ecosystem that we are a part of and depend on, this perspective seems to change. Multiple localized environmental disasters – heat waves, droughts and fires, deluges and floods – claim multiple lives, both human and non-human, on a daily basis. Many experts warn that the accelerated loss of biodiversity we are witnessing constitutes the sixth great extinction, this time caused exclusively by human activities. However, the hard threshold that distinguishes the “feasible” from the “impossible” in global environmental policy today, what guides decisions, is not the ecological or political effectiveness of a measure, but its profitability.

According to Andre Standing of the Transnational Institute, “Conservation finance has become the dominant ideology of most of the world’s biggest environmental NGOs. It is also heavily promoted by the World Bank, the United Nations and the European Union.” The author explains that “the basic premise of conservation finance is that saving nature and averting the climate crisis requires enormous funds, but money derived from public and philanthropic grants is woefully insufficient. (…) To do this, saving nature must be turned into a profit-making endeavour, appealing to what are known as ‘impact investors’..”

A radical shift in global environmental policy

In just a few decades, global environmental policy has taken a fundamental turn. In the 1960s and 1970s, it was an arena in which emerging environmental groups and movements fought against large polluting corporations, making use of judicial and legislative powers. They achieved convictions in courts and tribunals and regulatory norms in parliaments that were committed to limiting pollution and effectively repairing the damage. But from the neoliberal turn of the 1980s and 1990s, environmental policy began to shift from the prohibition and sanction of processes of pollution or destruction of nature that exceeded certain thresholds to a policy that bet only on “mitigating damage” – focusing on voluntary actions by companies. There was a transition from a policy that declared, in the name of the common good, that certain extractive or industrial ventures were unviable, to one that allowed the advancement of most extractive or industrial projects, prioritizing the processes of capitalist accumulation over human and ecosystem health. It shifted from the use of states’ regulatory capacity to an approach in which they only generate “market incentives” for polluters to voluntarily choose to implement mitigation actions.

Historically, and in contrast to the prospect of strict environmental regulations, mitigation was always seen as the most economic growth-“friendly” approach, and there was a tendency to appeal to it in the name of “freedom.” Supposedly, there is a hierarchical sequence in mitigation actions: first you have to avoid and, if that is not possible, you must seek to minimize damage. If that is not possible either, the previously affected ecosystem must be restored. The last link in the chain is the compensation of damage. However, the experience of several decades with carbon credits shows that often offsetting emissions becomes the first option, since it is the easiest path for large companies, more aligned with the profitability imperative that governs them. Critics such as the Global Forest Coalition (GFC) point out that this is likely to happen with biodiversity credits as well. In other words, necessary transformations in production systems to reduce their impacts effectively are avoided or postponed, thus aggravating the environmental crisis.

The big business of conservation

At COP16 in Cali, not only will the state of biodiversity be assessed. It will be the first COP on biodiversity to discuss the implementation of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, adopted during the fifteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP15) in 2022. And in this context, the issue of finance has been given centrality: according to transnational organizations such as the International Institute for Sustainable Development, The Nature Conservancy and the Global Environment Facility, one of the priority objectives of the event is to close a financing gap estimated at between 200,000 and 700,000 million US dollars per year and align financial flows with the Global Biodiversity Framework.

By crossing all spheres of life, neoliberal reason has also taken over global environmental governance. What guides decisions in environmental policy today is not even the direct cost of a measure, but the expectation or not of profitability. With regard to biodiversity markets, the major players in globalised capitalism are expecting huge profits: the World Economic Forum (WEF) estimates that over the next ten years, protecting nature and increasing biodiversity could generate business opportunities worth $10 trillion annually and create nearly 400 million new jobs. Investment funds such as the Boston Consulting Group even claim that globally forests would be worth up to 150 trillion dollars.

The rise of the financialization of conservation has not only transformed the way in which this phenomenon is addressed, but also the type of actors involved in the process. According to Standing, “People with backgrounds in finance, banking and business consulting are taking over the management of most of the big conservation organisations. Their governing boards are stacked with investment bankers, hedge fund managers and venture capitalists. Consequently, risky and opaque financial instruments, originating in financial markets, are being repurposed for environmental projects.” In the run-up to COP16, entities such as the World Economic Forum or websites such as Business for Nature are giving private companies a leading role. Framed in this same logic, the multi-stakeholder perspective that predominates today in the United Nations system has generated multiple transnational alliances between governments, banks and investment funds, large polluting companies and transnational environmental NGOs that are seen as simple “alliances of stakeholders”. The enormous asymmetries between its members are ignored and the very divergent interests that motivate them eclipsed. “Global biodiversity policy-making has increasingly allowed the very corporations responsible for environmental degradation to adopt market-based instruments, driven by strong corporate lobbying under the guise of ‘stakeholder participation’”, criticizes the Global Forest Coalition.

Compensation: a double-edged sword

This environmental policy is based on two myths that, despite being unfounded, are hegemonic in the environmental discourse: that economic growth can be “decoupled” from its impacts on nature and that it is possible to generate “win-win” solutions in the context of environmental protection – in which the environment wins and the investor wins. Euphemisms also abound. For example, we often talk about “nature-based” or “nature-positive” solutions, which in the first place means that through these solutions, nature will generate profits for investors. At the heart of the new environmental policies is the creation of credits as new commodities or “nature-based” financial assets.

A concept that was central to the creation of carbon credits and is now central to promoting biodiversity credits is that of “compensation”. To complicate things further in Latin America, in Spanish, “compensation” has a double meaning: on the one hand, “compensation” could be understood as a synonym for “recognition”. For example, as a historically just economic retribution for the care of the forest that indigenous peoples have carried out for thousands of years. But, in technical debates on carbon markets or biodiversity, the term is often used as a synonym for offsetting in the opposite sense. It is no longer the polluters who recognize those who have given care, but they absolve themselves of responsibility for the destruction they generate in a certain place, for a “compensation” payment aimed at the conservation of another place. Compensation understood as offsetting implies a spatio-temporal displacement that can be understood as a movement of externalization of responsibility: an example would be a mining company that destroys an Amazon biome in Brazil and “compensates” for this by paying money to “protect” another forest in Africa.

Clearly, this leads to several problems. One is the double land grabbing. First, the mining company appropriates the forest where it is going to mine, with negative consequences for the people who inhabited it (loss of habitat, food sovereignty, probably displacement and cultural uprooting). Secondly, the same mining company also appropriates the other space where it intends to compensate for this negative impact. Colonial and fortress conservation schemes predominate, which think of the protection of forests as protected areas or forests without people, expelling communities that live in interaction with the forest. This is a particularly sensitive issue, as it is scientifically proven that it is the modes of living of indigenous peoples, forest dwellers and local communities that best protect biodiversity – although the hegemonic discourse often accuses them of the opposite. Indigenous territories include more than one-third of the world’s intact forest landscapes (forest ecosystems that show little sign of habitat conversion or fragmentation). And deforestation in recognized indigenous territories is significantly slower than in other territories.

Standardize the epitome of diversity?

Second, the policy of offsetting – whether carbon or biodiversity – is highly questioned for its multiple levels of opacity. There has been a controversy for years about whether biotic carbon can offset the carbon emitted by industrial processes. Similarly, many scientists question the assumption that the biodiversity in one place can be considered “equivalent” to the biodiversity elsewhere. In other words, if the damage caused by an extractive project in a certain place can effectively be equivalent to the improvement or gain of biodiversity in another, distant place – the compensation place – which is the basis of legitimacy for this conservation strategy. Most ecologists admit that the substitutes used for this bargaining are grotesque simplifications of ecological relationships and non-human nature.

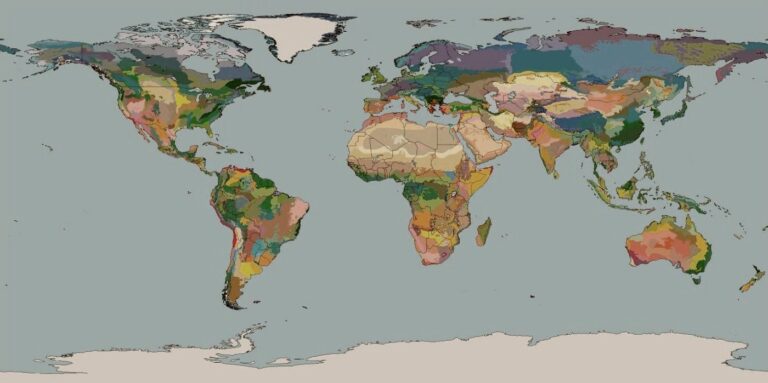

Biodiversity is defined as the variability of living organisms from any source, including but not limited to terrestrial and marine ecosystems and other aquatic ecosystems, and the ecological complexes of which they are a part: this includes diversity within each species, between species and the diversity of ecosystems. Obviously, this is not easy to quantify, and it is even more difficult to argue for ecological equivalence between components of biodiversity that differ in their type, location, and/or ecological context. The irony here is that biodiversity, the epitome of diversity, is forcibly subjected to a process of unification or standardization across a variety of metrics, in order to be transformed into a homogeneous and viable asset for finance capital.

In order to globalize biodiversity markets that are currently experimental (something that many intend to do at COP16 in Cali), these scientific questions would have to be discarded and a political agreement would have to be reached on what would be the appropriate metrics to calculate selected attributes of nature lost and gained and quantify “substitutes” or proxies (e.g., habitat variables) that can be combined and taken as representative of global biodiversity. This would supposedly make it possible to compare the damage caused to ecosystems in one place (the place of an extractive or productive investment) with the gains obtained elsewhere (the place of compensation), thus forcing an equivalence between the two.

From a political economy perspective, it can be observed that the capitalist valorization of biodiversity or its social production as an appropriable resource or marketable commodity for the purposes of capital accumulation involves a series of steps: from the production of specific aligned scientific knowledge to agreements of a political and ideological nature. And finally, for that valorization to work, for a country to be able to report its progress to the UN or for a company to be able to advertise a product as “neutral on biodiversity loss”, credibility needs to be built. This is where what is called “measurement, reporting and verification” comes into play – which is another very controversial field in the scientific debate.

This brings us to a third problem with biodiversity credits. It is highly uncertain whether they will be effective in protecting the biodiversity that actually exists. A scandal that erupted in 2023 around carbon credits suggest that: several studies showed that their effect on reducing deforestation was zero in most of the cases studied and that certifying companies had inflated baselines. In such a way, the result could easily even be an increase in net emissions since those had supposedly been “offset”, in a context of high vulnerability of the verification methods applicable in such complex matters.

But despite these many doubts, the United States and the European Union have included compensation for biodiversity losses in their environmental legislation. It is normally included in the framework of the approval of large projects in the context of environmental impact studies. In addition, voluntary biodiversity markets, which already exist on an experimental basis in 64 countries around the world, allow large companies and financial institutions to reduce their operational risks. Offsets help companies with significant ecological footprints maintain their legal and social licenses, (deceptively) improve their image, and reduce credit risk.

Biodiversity policy and indigenous peoples

There is a broad consensus on the critical role of indigenous peoples, pastoralists, artisanal fishers, peasants and Afro-descendant communities in the effective conservation of biodiversity. Most indigenous peoples have lived in reciprocity with forests of great biodiversity and have actively cared for them for thousands of years, practically without money or similar means of exchange, due to their modes of living based on hunting, gathering and small-scale farm farming in rotating places. This extraordinary capacity is based on a different philosophical understanding of the relationship between society and nature, which places humans not above, but as an interdependent part of their environment. It is significant that, although they are mostly not completely disconnected from capitalism or outside of it, these peoples do not live “for” capitalism, they are not subject to the imperatives of accumulation. Today, money is still not central to their reproduction, even though it contributes to it to an increasing extent. This is due to the bioprecariousness that results from the multiple onslaughts of the capitalist world on their territories: both the expansion of the frontiers of extractivist destruction and the epistemic violence that labels their philosophies as “beliefs” and their modes of living as backward, primitive and “to be overcome”, instead of recognizing them as truly sustainable.

There are those who see biodiversity markets as an opportunity for indigenous peoples. However, a systematic analysis of the 2023 voluntary biodiversity markets concludes that none of the programmes examined were developed by indigenous people, that most programmes did not set comprehensive requirements for obtaining free, prior and informed consent, nor did they involve models of co-ownership, partnership or benefit-sharing with communities. Another problem is that the technicalities and opacities that characterize these markets and their volatility in the financial markets prevent peasant, indigenous or forestry communities from knowing with certainty who they are dealing with and under what conditions.

There is a high risk that in the context of COP16, the hype generated around biodiversity credits will prevent attendants from discussing politics that, outside of markets, can be truly effective in preserving biodiversity, and that reposition sustaining life at the center of the scene. That such important issues as the possibility of strong public regulation of polluting productive activities and extractivism are marginalized from the debate; or a transformation of the global agri-food model towards agroecology; or actions to restore degraded forests and ecosystems that generate direct employment for local communities and not for those who work in the world of finance. Today we need politics that, instead of trying to “include” indigenous peoples in the logic of profitability so that they become shareholders of their own territories, bet on strengthening their modes of living on their own terms, to rebuild and restore their material bases of reproduction and knowledge. Politics that recognize their historical contribution and address the need for reparations, both material and structural, for centuries of grievance, violence and destruction.

It remains to be seen to what extent the host of this COP16, Colombian Minister of Environment Susana Muhamad Gonzalez and the broad social basis of the Colombian government, even intend to divert or succeed in disturbing the expected move toward the commodification of biodiversity. For now, it is important that organized society and ecologist movements do not simply delegate the protection of our web of life to UN-spaces, corporations and banks. Beyond advocacy work, multi-scale action is at the order of the day, beginning at the territorial level and in our subjectivities, to build barriers against the imperatives of profitability. Peoples-to-peoples initiatives that prefigurate how environmental justice and climate reparations can be built in practice across continents, horizontally and in a perspective of an eco-territorial internationalism are needed, to show effective pathways of direct action beyond the complex multilateral arena. A change of the very logic that drives environmental politics today is necessary at all levels, one that foregrounds relational worldviews, care and reciprocity with Nature instead of the patriarchal, modern impulse to dominate and destroy it. Even the idea of “conservation” itself should be called into question, as it remits more to a thing than to a living subject with which humans have to urgently re-relate. That might all seem difficult at first glance. But when it comes to protecting life, no sacrifice, no challenge can be exaggerated.

Originally published at: https://radicalecologicaldemocracy.org/peace-with-nature-cop16-in-cali-and-the-defense-of-biodiversity/