The white gaze permeates many aspects of even the most critical disciplines. In this piece, we offer some thoughts on how we might reclaim what the university could be – a place that equips people with the knowledge they need to unlearn/unmake/dismantle the framings and worldviews that lend themselves to white supremacy and other forms of oppression more broadly.

by Collective of critical geography and development scholars*

Around the world, people are coming out to denounce systemic racism in their institutions and in society more broadly. The Covid-19 pandemic has offered a magnifying lens to the deep-rooted inequalities and injustices prevalent in society. It has also shown how inequalities, such as those along racial, gender, and class lines, are reinforced and compounded in a relatively short time span in the efforts to return to “normal”. Returning to business-as-usual is precisely what institutions, governments, and corporations are so desperately seeking. Yet, the world before and during the pandemic was/is premised on white supremacy, colonial legacies of natural resource extraction and bondage of cheap labour. Consequently, returning to “normal” is not something that we should ethically and politically aspire for. As Indian writer Arundhati Roy writes, the pandemic should be a “portal” to deconstruct, and transform the world that we knew before. This does not mean making business-as-usual more comprehensive, holistic, or inclusive. Rather, it involves the harder work of “un-learning” and “un-doing” the current model of productivist and extractivist development disguised as modernity and “progress”. By prioritizing careful attention and consideration of multiple ways of knowing and relating to the world, we can be better positioned to support ongoing struggles in re-building a world premised upon justice above all else.

The Responsibility of Universities and other institutions of higher learning

Universities and institutions of higher-learning have an important responsibility in these “unlearning” and “rebuilding” processes as they offer privileged spaces for enhancing critical thinking in dialogue with constant societal change. Improving societies by prioritizing justice is a core task of universities in the advancement of science and technology as collective commons. After all, what good is generating knowledge if it cannot be (re)produced, accessed, and understood by all? Even if scholars have advanced many long and fruitful discussions on how to break free from colonial legacies and extractive development models, these initiatives risk losing their meaning if they are inscribed into an academic environment which is both principled and conditioned upon competition and a growth-oriented knowledge economy. Much of the wealth of academic insights get sucked into the aspirations of an expansionary university in competition within a globalized academic industry. This hollowing-out takes place due to the ways by which the process of generating knowledge (including the labour of researchers and their collaborators) gets parameterized and packaged into predetermined “outputs” as stipulated in grant proposals and departmental performance rubrics. These quantified metrics are then used to justify academic positions (and indeed whole departments). The pressure to aspire for growth within academia risks knowledge getting detached from its situated context, losing its meaning, and instead becoming an end-product in itself.

Worse still, this highly uneven process generates cultures of distrust, hierarchy, competition, and fast-scholarship in the race to produce more in the least amount of time. While obviously reflecting different contexts of privilege, the underlying mechanisms and logic behind this production process is no different from the discipline of a factory floor, in which researchers extract knowledge and are themselves the subject of extraction. This hierarchy of extraction can be seen when, for example, junior scholars, themselves engaged in extracting knowledge from third parties for their own projects, may be obliged to undertake menial tasks unrelated to their own research and which serve to benefit only their superiors. In addition, knowledge production in academia is reserved to those who are the best-placed to compete in this game, which is often to the disadvantage of women, people of colour and junior researchers, and those without academic credentials (including local community members who are often the “subjects” of research with whom especially social science scholars interact with in advancing either theoretical or applied knowledge).

This factory-floor model of academic production rooted in asymmetrical power relations replicates a singular way of shaping and understanding knowledge generation. It is premised upon optimizing knowledge products as outputs dependent upon the labour (e.g. academic faculty and support staff) and resources (e.g. grant funding, partnerships, networks, and research “subjects”) required to produce these outputs in the most efficient way. This extractive process of mobilizing labour and resources for knowledge production cannot be centred on any individual, but is situated within a cutthroat industry where peer-reviewed journal impact factors, publication numbers, successful grant applications, global partnerships, graduate programs and percentage of successful graduates and even the number of followers on twitter are all instrumentalized for the purposes of showcasing which university, which department, or which faculty member wins the ‘gold medal’ in the globalized academic Olympics. The competitive tendency here already takes extraction and instrumentalization of relationships in academic collaboration as a normalized starting point and then builds on this mode of operation as a way to gain a greater share within the knowledge economy.

The instrumentalization within academia extends beyond internal collaborations within the academia to historically colonial relations of academics and their research “subjects” in the field. The relationship between historical colonial legacies in the perpetuation of the knowledge economy is indeed a serious cause for concern. Indigenous Maori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith argues, for instance, that social science “research” is itself one of the “dirtiest words in the Indigenous world’s vocabulary” having been inextricably linked historically to European imperialism and colonialism in terms of how “knowledge about indigenous peoples was collected, classified, and then represented back to the West.” Bhambra and colleagues take this further by stating that “[t]he foundation of European higher education institutions in colonized territories itself became an infrastructure of empire, an institution and actor through which the totalizing logic of domination could be extended; European forms of knowledge were spread, local indigenous knowledge suppressed, and native informants trained” (p.5).

This white gaze of a singular understanding of the world then gets reproduced through the production metrics and standards imposed by the knowledge economy. Implicit extractivism in the academy operates by failing to recognize and then act upon the asymmetrical ways that knowledge extraction preys upon the precarious positions of more vulnerable scholars. As scholars in Development Studies in particular, we acknowledge how insights from the so-called “Global South” have historically served and continue to serve Northern universities and research institutes. This process of translating diverse knowledges into a singular easy-to-digest narrative is precisely how white supremacy circulates, even unconsciously, in reproducing the homogenizing and simplifying patterns that have shaped colonial development since the 15th century. The factory-house model of organizing and optimizing knowledge generation follows the tradition of resource exploitation since colonial times and as such, carries with it the white gaze of what counts (and doesn’t count) as legitimate knowledge. A white gaze extends to the built-in hierarchy of knowledge producers propagated by national research foundations, where non-academic knowledge producers and researchers from the Global South are accepted only as informants or field assistants, with an incredibly skewed scale of remuneration. Ultimately, the academy extracts wealth from marginalized communities and organizations and justifies these logics by making those not under the accepted institution marginal, invisible, underfunded and with limited access to knowledge production resources.

Academics can no longer be permitted to surf this wave of deeply extractivist practice in how knowledge is generated. Transforming the university requires not only turning the mirror upon ourselves as academics in reflecting upon our practice, but also more fundamentally in actively dismantling the knowledge economy that is structured in the constant prospection, appropriation, and standardization of intellectual labour. Decolonizing the university means collectively re-establishing “the terms upon which the university (and education more broadly) exists, the purpose of the knowledge it imparts and produces, and its pedagogical operations”. Such an effort requires fundamentally different ways of political organization in how knowledge gets generated. In other words, we academics must self-reflect at the same time as we act to transform the university and society more broadly away from systemic injustices. Academics have a notorious tendency to pensively sit back and comfortably theorize on ways to dismantle systems of inequality, even as we paradoxically benefit from those very same systems of inequality in perpetuating the knowledge economy. Consequently, our privileged capacity to self-reflect risks replicating the very structures some of us write so vehemently against, particularly in the competitive arena of instrumentalizing academic relationships for the purposes of career advancement. The professionalization of social justice critique becomes trapped within a “hall of mirrors” whereby the emancipatory potential of co-produced knowledge gets neutralized by the predatory tendencies of the academic industry in which “knowledge products” are continuously stacked as if on an endless pile.

“Decolonization” – the making of a Buzzword?

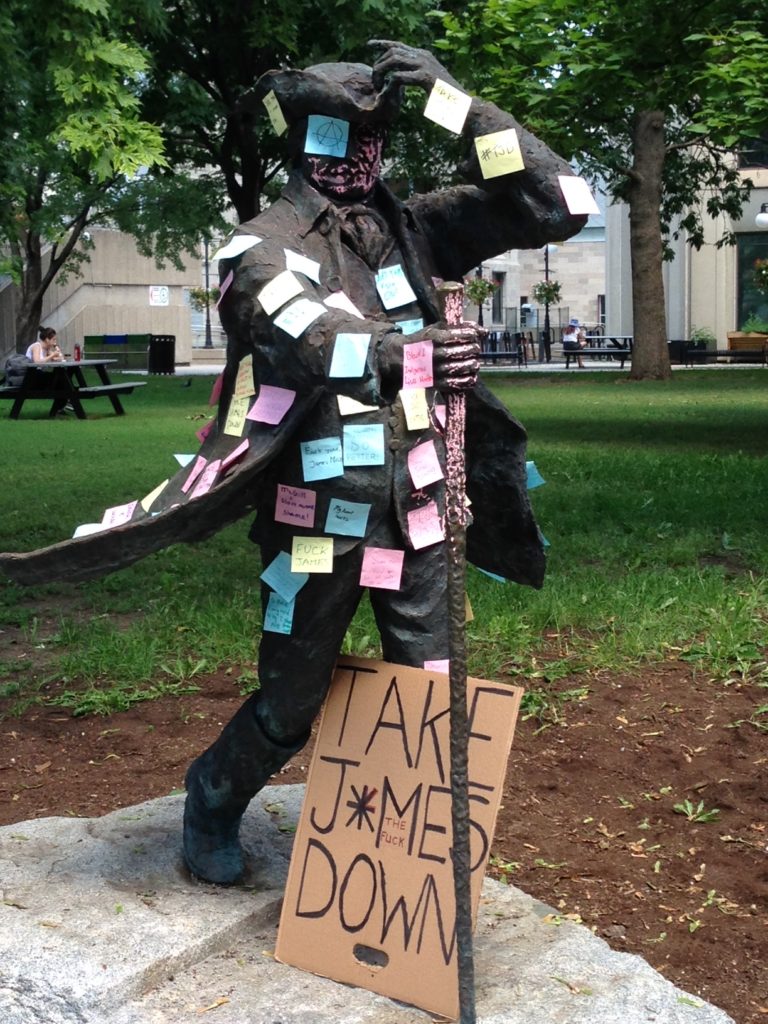

Having recognized these tendencies, the academy’s approach to responding to these challenges has been to performatively showcase universities as being “inclusive.” “Decolonization” becomes a topical buzzword for which academic pursuits can be channeled to tap into new sources of knowledge outputs for more socially-just economic growth in the knowledge economy. This new “decolonial frontier” is violently at odds with what decolonization is actually about; the frontier becomes a new way to extinguish any possibility of real transformation. As Tuck and Yang have argued, decolonization is not a metaphor; it must never be co-opted by being restricted to a checklist composed of “diversity and inclusion” statements by the university, institutionalized “codes of conduct”, or integrating “decolonial” curricula into more holistic graduate programs and the like. For Tuck and Yang, decolonization refers specifically to restoring native lands that were violently usurped in the process of settler colonialism. Elsewhere, it refers to dismantling the structures of European imaginaries that have come to shape how “development” is defined and understood.

If recognition exists about these structural problems so ever-present in the expansionary aims of the academic industry, why does it remain so hard to impart long-lasting change that goes beyond optics? Like broader society as a whole, the answer lies in the uneven ways that power operates to discipline those who complain or deviate from standard practice in the academic profession. For instance, speaking out about some of these concerns has disproportional implications for junior scholars, and especially women and people of colour, who risk compromising their future prospects in the academy by exposing any of its potential flaws. On a broader scale, many research participants in the generation of knowledge are not even afforded a space to enter into the academy’s walls. They remain as “missing co-authors”, perpetually denied legitimacy to change the academy from within. Rather, they are charged with being essential to the research enterprise; essentially inputs for the production of knowledge products. Moreover, it is they who must absorb the implications of these “products” that inevitably shape their own livelihood capacities and potentials.

To re-emphasize, this intervention is not targeted to the specific actions of individual scholars (though these do need to be held accountable), but is rather exposing a systemic problem. As academics ourselves, we are equally complicit, and feel that it is our duty to support any type of alternative that confronts the root-causes of extractive practices in the academy. While saying this, we also recognize that writing an intervention like this comes from a position of privilege, which would not be afforded to many others, but this is precisely why we do this. Just as remaining silent about one’s own racial privilege, while claiming to “not be a racist” is how white supremacy continues to thrive, remaining silent about one’s privilege in the academic class structure is complicity in its reproduction. Either we collectively take active steps to end these exploitative ways of doing research or we stop making performative claims that we are somehow making the university more just, inclusive, and diverse.

How do we then build counter-power to address the exploitative logics underpinning the academic endeavour and to subvert any attempt to tokenize what decolonization of academia is about? Changing current academic culture and its underlying perverse incentive structure requires us to collectively stand up against an unfair system, while taking into account that any type of fundamental change is slow, therefore placing the onus particularly on the more established scholars with more or less fixed positions to change the rules of the game. Given the privilege of established scholars, this is of course a delicate process that must be conducted with great transparency and accountability to avoid reproducing new forms of inequality. Building resistance to business-as-usual does not require reinventing the wheel. We must join with feminist scholars who unequivocally state that “cultivating space to care for ourselves, our colleagues, and our students is, in fact, a political activity when we are situated in institutions that devalue and militate against such relations and practices” (p.1239). Likewise, “slow scholarship”, which refers to transforming academic institutions from the ground-up, by actively resisting against “the culture of speed in the academy and ways of alleviating stress while improving teaching, research, and collegiality”, offers a path for fundamentally transforming the power relations of knowledge production.

Moving forward

There is an increasing wealth of resources, strategies, and alternatives that are being advanced to stimulate fundamental structural changes in how the academy operates. By no means an exhaustive list, below we identify some key examples of how to move forward. These examples are even more relevant in a context of deep uncertainty and increasing precarity as a result of the global pandemic.

- A manifesto for “building collectives of care rather than mere departments” by unlearning the boundaries of academic discipline;

- Developing a ‘moral economy’ of knowledge co-creation that prioritizes the process over the end outcome and encourages timeless and caring spaces of interaction for genuine creativity, collegiality, and joy to be the drivers of knowledge generation;

- Building an “ethics of mentorship” in which established scholars cede place to the learning trajectories of junior scholars and to prioritize quality and process over quantity;

- Re-commoning knowledge for all by rethinking publication strategies to damage the pocket books of for-profit publishers and synchronously redefining and requalifying our “production”;

- Building meaningful, non-extractive, and care-ful partnerships and collaborations for engaged social research. This requires engaging different publics, being comfortable to refine or even reject earlier ideas, fostering safe spaces to be more vulnerable about fears and emotions in the research process, directly linking research outcomes with activism and advocacy in highly political arenas, and generally amplifying the potential impact of our scholarship rather than moving on to the next product that “counts” to administrators”;

- Reparations and redistribution of research funding such that recognition of non-academics in general and academics of the Global South is not just symbolic. A systemic reorganization process is required within the academy to recognize the shared knowledge producing labour of all partners in the process – from cleaners within the walls of the institute to participants in research endeavours in all corners of the world and in contributing to the knowledge commons;

- Being accountable to the responsibilities that come with privilege, for example by taking the lead in shaking up evaluation protocols and shifting how accountability and evaluation metrics are established at the university and departmental level (“good enough is the new perfect”) or by ceding place in the publication race and instead empower and embolden younger and more precarious scholars to advance this agenda in their institutes and from their own lived experiences;

- Building counter power through Internationalist unions of intellectual workers, involving unionisation beyond the established Western trade unions which often just support the privileges of the few university employees with tenure;

- Making the work of universities function as integrated parts in a very different social metabolism – meaning that social reproduction both of research and of the university upkeep itself becomes an integral responsibility for all those affiliated with the university. In other words, this implies that the work of maintaining the academic endeavour cannot be cost-shifted to cheaper or more precarious labour, but must be a core responsibility of those who live and breathe within the university.

*Vijay Kolinjivadi is a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute of Development Policy at the University of Antwerp.

Gert Van Hecken is Assistant Professor at the Institute of Development Policy (IOB), University of Antwerp (Belgium) and Research Associate at Nitlapán-Universidad Centroamericana (Nicaragua).

Jennifer Casolo is Research Associate at Nitlapán-Universidad Centroamericana (Nicaragua), and at the Pluriversidad Maya-Ch’orti’ (Guatemala).

Shazma Abdulla is a writer, innovator, and community organizer who focuses on social inequities, racial justice, and spatial justice. She is affiliated with the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University in Canada.

Rut Elliot Blomqvist is a doctoral candidate at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden exploring the transdisciplinary fields of utopian studies, environmental humanities, and political ecology to not only consider the structure and meaning of environmentalist political visions but also the role of literary and cultural theory in these fields.

**We are incredibly grateful to Frances Cleaver, Tomaso Ferrando, Frédéric Huybrechs, Nathalie Pipart, Hanne Van Cappellen, and Juan Sebastian Vélez Triana for useful comments and suggestions provided on earlier drafts.