by Iokiñe Rodriguez and Mirna Inturias

Introduction

The adoption of Bolivia’s new political Constitution in 2009 marked the birth of a new plurinational state. One of the most important constitutional changes was a new state system of territorial division that recognises departmental, municipal, regional and indigenous autonomies as new plural forms of political organisation seeking to decentralise decision-making power and the management of public funds, wresting them away from central government. Whereas departmental, municipal and regional autonomy can apply within the pre-2009 territorial division of the state, simply being juxtaposed over former departments, municipalities or regions, indigenous autonomies pose a greater challenge, as they often overlap with more than one municipality or department and therefore necessitate greater institutional and legal changes.

The indigenous autonomy model acknowledges the rights of indigenous peoples to self-determination, self-government, the perpetuation of their culture and the consolidation of their lands within the framework of the unified state. It also opens the way for the recognition of Original Indigenous Peasant Autonomies (AIOCs). To date, only three out of more than 30 claims that have initiated proceedings to establish new AIOCs have been granted rights from the state to form Autonomous Indigenous Peasant Governments (GAIOCs). These new forms of government require further institutional and legal changes to ensure a genuine transition from a modern, liberal state model to a plural, diverse one.

Among other things, this process involves expanding the liberal conception of democracy to an intercultural one, which under the new electoral law entails interaction between three forms of democracy: representative, direct/participatory and ‘communal’. The latter referres to democratic processes taking place at the local community level through consensual, deliberative decision-making and respecting traditional decision-making structures such as community assemblies, councils of elders and the customary rules and regulations of indigenous justice systems. This new democratic concept creates leeway for the emergence of new forms of knowledge, epistemologies and indigenous practices, hitherto absent from Bolivia’s democratic model and the construction of new intercultural forms and structures of governance. However, the way forward to true ‘demo-diversity’ (Santos/Exeni 2012), i.e. an environment in which different concepts, knowledge and democratic practices can come together, is still far from clear.

We will discuss the current challenges in constructing an intercultural democracy in Bolivia in the light of the struggle of the Monkoxɨ, an indigenous people from Lomerío, to gain political autonomy. The Monkoxɨ formally petitioned the state for political autonomy in 2009, and major recent headway in their claim suggests that the national authorities could soon recognise their autonomous government.

If their claim proves successful, the Monkoxɨ will face the serious challenge of progressing in their construction of a model of intercultural democracy that is at odds with a range of political, economic and cultural factors. This case study examines these tensions and the ways in which the Monkoxɨ are deploying various cultural and political strategies in an attempt to consolidate a truly community-based, plural model of democracy in Lomerío. The information we present summarises the results of a participatory assessment we carried out with the Monkoxɨ in 2018 to evaluate the strategies they had employed over the past four decades to consolidate their territorial control and political autonomy in Lomerío (see Inturias et al. 2019 for more details). For this purpose, we used a Conflict Transformation Framework developed by Grupo Confluencias to map the changes brought about by the Monkoxɨ over time, focusing on the parameters of cultural revitalisation, political agency, local governance, control of the means of production and environmental integrity (Rodriguez et al. 2019, Rodriguez/Inturias 2018). This assessment was part of an international project called ACKnowl-EJ (Academic and Activist Co-Produced Knowledge for Environmental Justice), which examined how resistance movements across the world are helping to bring about just transformations to sustainability from the bottom up (http://acknowlej.org).

The Monkoxɨ dream of Nuxiaká Uxia Nosibóriki (their own form of government)

The communal indigenous territory (TCO) of Lomerío covers 256,000 hectares of land dominated by Chiquitano dry forests in the administrative department of Santa Cruz in lowland Bolivia. Lomerío is home to around 7,000 indigenous Monkoxɨ living in 29 communities ranging in size from 100 to 1,500 inhabitants.

The Monkoxɨ define Lomerío as a refuge, an area to which their ancestors escaped in colonial times to flee from Jesuit missions. Yet, much to their detriment, shortly after the missionaries were expelled in 1776, Bolivian mixed-race mestizo and white landowners took their land for agriculture and animal husbandry, forcing the Monkoxɨ to work as slaves on rubber plantations. They were cruelly exploited well into the late 20th century, so their refuge became their prison for more than a century.

Despite this oppressive past, or perhaps because of it, the Monkoxɨ are one of the most emblematic indigenous peoples in Bolivia’s lowlands in terms of their political strength and organisation. They have a long history of resistance to the colonial state and land tenure system. Their organised resistance started in 1964 when they formed the Agrarian Peasant Union, before going on to play an instrumental role in establishing the Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of Bolivia (CIDOB) in 1982 and then the Indigenous Organisation of Native Communities of Lomerío (CICOL) in 1983. In the late 1980s, the Monkoxɨ were the first indigenous nation in Bolivia to develop community forestry as a form of territorial control, and in 2006, after a long struggle, they successfully won the legal rights over their communal indigenous territory, which CICOL is legally mandated to safeguard.

As is clear from the statement below, the final component to free themselves from oppression would be the right to self-govern their territory:

“Our grandmothers and grandfathers gave their lives to give us a territory where we can be free, where we can make the dream of having our own form of government real, and thus turn our refuge into our road to freedom and our desire to live well. This is what we call: Nuxiaká Uxia Nosibóriki” (Masay, Elmar/Chore, Maria, 2018:14).

Thus, in 2008, the Monkoxɨ were the first indigenous nation in Bolivia to use the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to legally underpin their public proclamation of the first autonomous indigenous territory in Bolivia. In 2009, at a General Assembly attended by their 29 communities, they drafted and approved their autonomy statutes and launched their legal claim to rights to autonomy. In parallel, Monkoxɨ leaders actively participated in the 2008 constitutional reforms to ensure that indigenous rights to autonomy were adequately accounted for in the new framework of the Plurinational State of Bolivia.

The key elements of the Monkoxɨ nation’s autonomy statutes are as follows:

- Definition of the ancestral territory of Lomerío as the geographical limit of their government.

- Defence of communal democracy as the main form of collective decision-making.

- Emphasis on the principles, values and norms of communal and territorial life, such as freedom, sharing (minga or bobikix), equity, reciprocity, redistribution, and solidarity.

- Establishment of besiro as the official language and Spanish as the second language.

- Designation of a General Assembly including representatives of the 29 communities, as the top decision-making authority.

- Importance attributed to customs, rules, norms and indigenous justice when regulating day-to-day communal life.

- The definition of communal economy as the desired form of development, aimed at enabling the Monkoxɨ nation to live well, i.e. achieve what they call Uxia Nosiboriki/Buen Vivir), respecting Mother Earth, the spirits of the forest (Jichis) and living in harmony with nature (CICOL 2015).

In May 2018, the Plurinational Constitutional Tribunal (TCP) ruled in favour of the Monkoxɨ statutes, yet the Monkoxɨ model of self-government still faces a number of internal and external challenges before it can effectively be applied.

Challenges to self-government in Lomerío

External factors

The external tensions concern the fact that despite the transition to a new plurinational state, state structures and institutions, economic frameworks and dominant cultural values are still essentially modernist and colonial.

This is certainly the case regarding the national developmental model, which continues to impose a narrowly defined economic rationality on the use of natural resources. The state is a long way off from turning the Living Well (Buen Vivir) narrative into a reality (despite such an approach being enshrined in the new Constitution). One way this is reflected in Lomerío is in the strong hold retained by market forces and Forestry Department bureaucrats, which dictate the rules governing community forestry, limiting the Monkoxɨ nation’s effective control over this activity. On top of this, although the Monkoxɨ have legal ownership of their territory, the subsoil remains the property of the state, and all the mineral resources in Lomerío have been designated for mining concessions, without heeding prior informed consent procedures.

In addition, the national executive has given indigenous nations very little help in advancing their autonomy claims. Far from it, in fact, so progress has been very slow. To keep their autonomy claims on track, indigenous nations have had to adapt their autonomy statutes and structures to new regulatory frameworks, such as the 2010 Autonomy and Decentralisation Law (No. 031/10), which makes the whole procedure very complex and cumbersome. The National Executive, the Plurinational Constitutional Tribunal (TCP), the Legislative Assembly and the Supreme Electoral Tribunal each impose a different set of requirements. In addition, many of the public servants involved in granting autonomy rights continue to think and act in accordance with monocultural regulatory frameworks, which in practice has meant placing obstacles in the way of indigenous forms of autonomy by pressuring them to opt for the short route to self-government, namely conversion to municipal or departmental autonomy (Avila 2018). All these factors explain why it took the TCP 10 years to grant the Monkoxɨ nation its autonomous status. So, although that is a great accomplishment for the Monkoxɨ people, the process is far from over.

Internal factors:

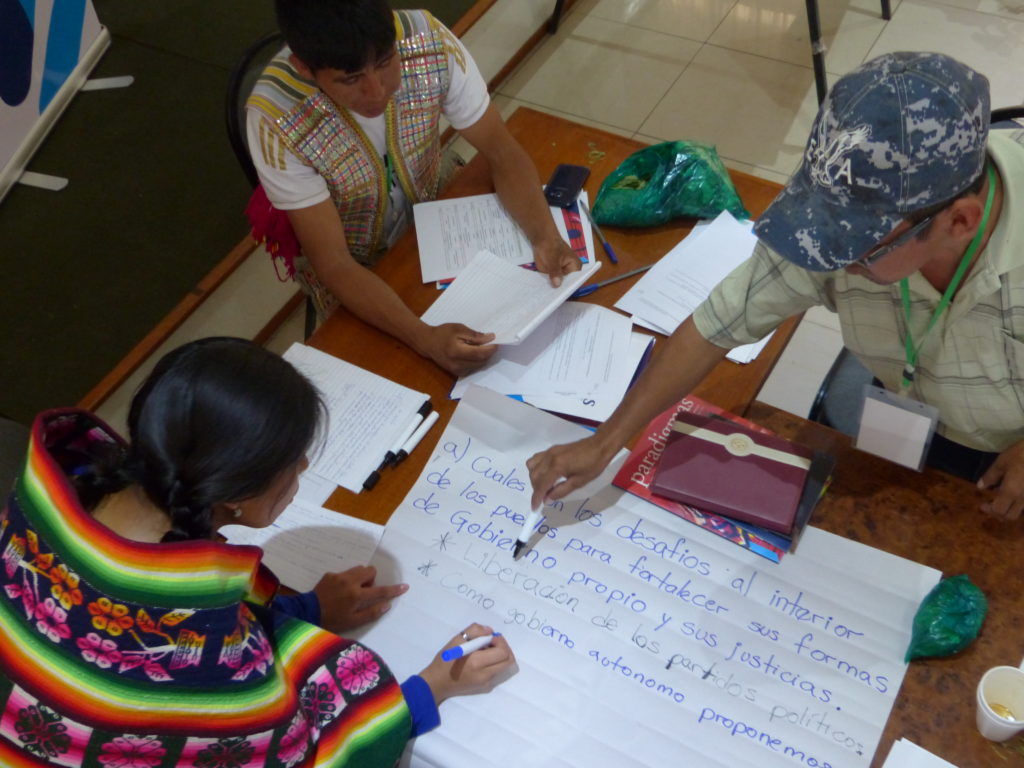

Internally, the biggest challenge for the Monkoxɨ nation’s bid for autonomy will be to ensure that its communal democracy system succeeds in directing its indigenous government, avoiding divisive party politics and giving precedence to customary norms and regulations. Currently, there is strong internal resistance to the model of indigenous autonomy on the part of the hegemonic Monkoxɨ families currently running the municipal government, which question a communal democracy model. This group favours maintaining a representative democracy model and regards indigenous custom-based decision-making procedures and justice systems as backward and primitive. Consequently, it has been pushing for municipal autonomy as an alternative form of local government. Underlying this tension between different models of democracy are conflicting values and world views about what it means to be indigenous, this being yet another expression of coloniality and modernity in Lomerío.

This tension between modern and more traditional indigenous values poses challenges for the indigenous autonomy process at other levels. Firstly, the Monkoxɨ principles, values and norms of communal and territorial life, such as sharing, equity, reciprocity, redistribution and solidarity, are not necessarily the principles that guide community life. On the contrary, in many communities individual interests and benefits connected to the use of many resources in their territory, such as forests, prevail, which not only creates strong inter and intracommunity conflicts, but is also threatening the integral use of the environment and territory. Secondly, in terms of cultural vitality, central aspects of Monkoxɨ identity, like its besiro language, are struggling to survive. Thirdly, and linked to the above, the younger Monkoxɨ generations are growing up with little awareness of their own history and cultural ties to the land, lack the leadership qualities to manage and safeguard their territory in the future and are attracted to ‘modern’, urban lifestyles.

Moving forward

Despite these challenges, this complex economic, political and cultural context has not deterred CICOL, as the legal custodian of Lomerío, from taking forward the mandate from the 2009 General Assembly to consolidate an autonomous Monkoxɨ government. However, it has taken perseverance and inventiveness to develop a variety of strategies aimed at addressing as many of these challenges as possible. Some of these strategies have aimed to make progress in securing autonomy, others have been set out to tackle the internal factors that might threaten the viability of the autonomy process in the long run.

One key element in advancing the autonomy claim has been the formation of sustained partnerships with various support organisations that can help to strengthen the technical and financial aspects of the demand. The recent creation of strategic links with key players in the central government, such as the minister and vice-minister of autonomy, to jointly evaluate the challenges and opportunities associated with Monkoxɨ indigenous autonomy has boosted the profile of their claim both nationally and internationally and accelerated some of the procedures involved (Inturias et al. 2016). Likewise, creating opportunities to share experiences with other indigenous nations also in the process of claiming autonomy has been instrumental in devising joint strategies that can put pressure on the government to overcome the administrative hurdles standing in the way of the final approval of their demands (Inturias et al., 2019). One example of this is a recent change to the autonomy application procedure that eliminates the need to hold a second local referendum in territories with a majority indigenous population to validate the autonomy statutes after the National Executive has approved them. This change is crucial in cases like that of Lomerío, where a group opposing the indigenous autonomy model could use a second referendum to sabotage and invalidate the Monkoxɨ nation’s claim.

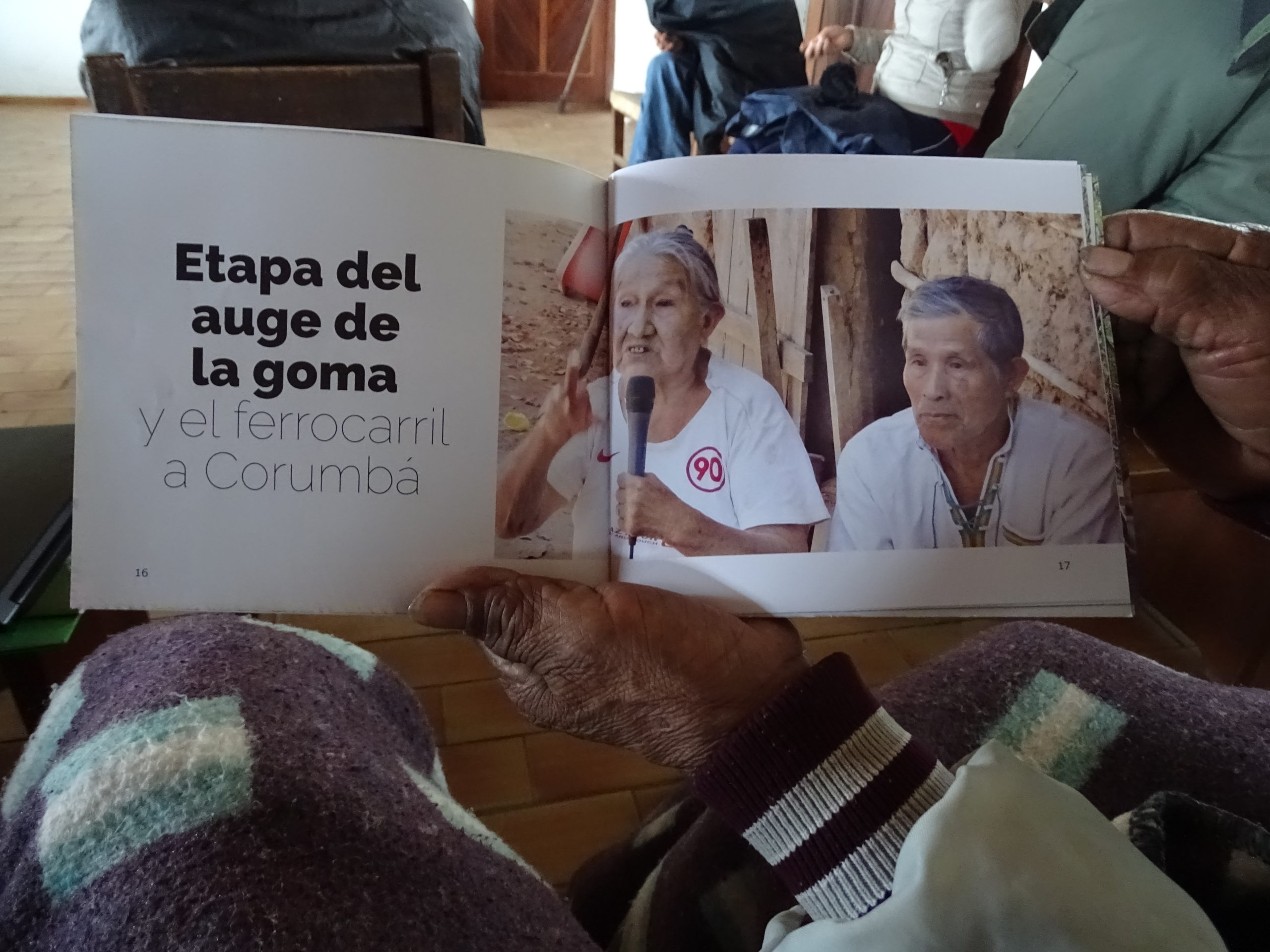

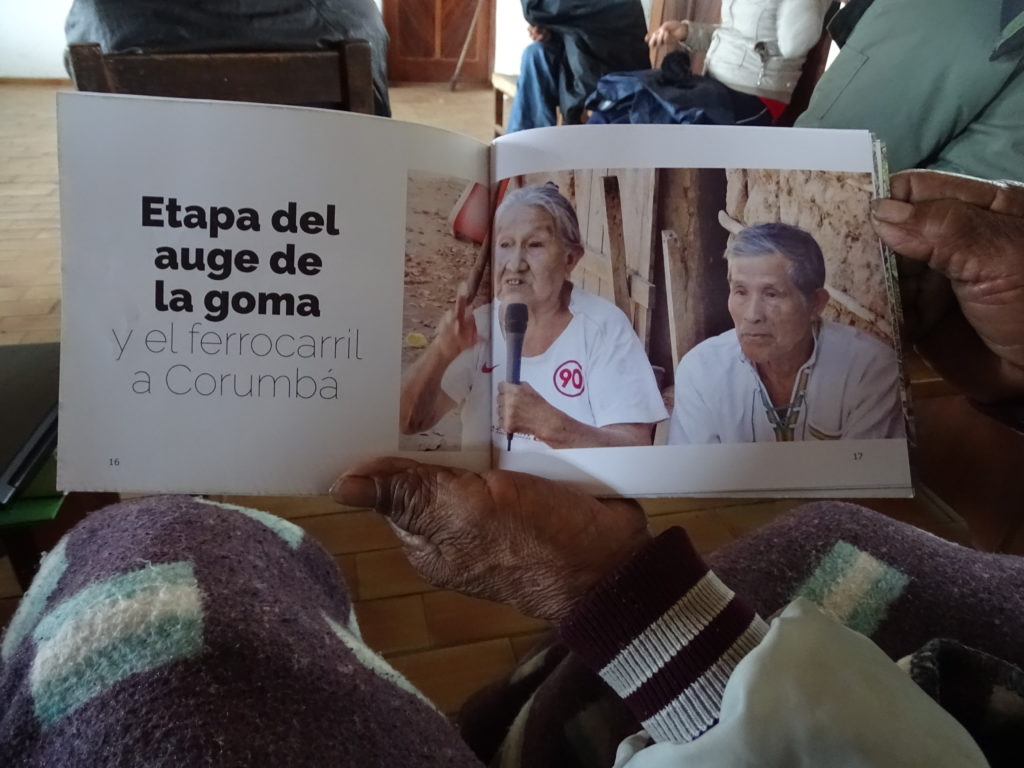

With regard to dealing with internal threats to the autonomy process, CICOL has been particularly concerned about the processes of cultural change and shifting identities among the younger generation. Activities carried out to tackle this problem have involved developing participatory processes to reconstruct local history (Pena et al. 2016) and capacity building based on indigenous leadership values and new projects, in a bid to revitalise the besiro language. That said, CICOL and the Monkoxɨ still need to address a number of pending issues to ensure an effective transition to an intercultural democracy in their territory. These issues include:

a) deciding the type of public communal administration that the indigenous government will implement to avoid replicating the municipal approach or colonial-style public policy framing;

b) considering the future model of development for Lomerío and how to effectively create a just, environmentally sustainable communal economy; and

c) working out, once an indigenous government has been established, how to ensure a mode of effective coordination with other regional and national government authorities that is sensitive to cultural differences and diverse forms of knowledge.

References:

Avila, H. (2018), Foreword in Flores, E. (2018). Sueños de Libertad. Proceso autonómico de la Nacional Monkoxɨ de Lomerío. CICOL-CEJIS, Santa Cruz de la Sierra.

CICOL (2015). Estatuto Autonómico de la Nación Monkixi de Lomerío. CICOL/CEJIS, May 2015.

De Sousa Santos, B./Exeni, J. L. (eds) (2012). Justicia indígena, plurinacionalidad e interculturalidad en Bolivia. Ecuador: Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

Inturias, M./Rodriguez, I./Valderomar, H./Peña, A. (eds) (2016). Justicia Ambiental y Autonomía Indígena de Base Territorial en Bolivia. Un dialogo político desde el Pueblo Monkox de Lomerío. University of East Anglia, Nur University, Grupo Confluencias and the Ministry of Autonomy, Bolivia.

Inturias, M./Rodriguez, I./Aragon, M./Masay, E./Peña, A. (2019). Lomerío: autonomía indígena de base territorial como fuerza de transformación de conflictos socioambientales, in Inturias, M./von Stosch, K./ Balderomar, H./Rodriguez, I. (eds) (2019). Bolivia. Desafios socioambientales en las tierras bajas. Department of Investigative Social Science at Nur University, Bolivia. Available at: http://www.iics.nur.edu/publicaciones/editorial-nur/287-bolivia-desafios-socioambientales-en-las-tierras-bajas.

Inturias, M./Vargas, G./Rodríguez, I./García, A./von Stosch, K./Masay, E. (eds) (2019). Territorios, Autonomías, Justicias. Un dialogo desde los gobiernos autónomos de Bolivia. Department of Investigative Social Science at Nur University, the Vice Ministry of Autonomy, University of East Anglia, Santa Cruz de la Sierra.

Masay. E./Chore, M. (2018). Presentation in: Flores E. (2018. Sueños de Libertad. Proceso autonómico de la Nacional Monkoxɨ de Lomerío. CICOL-CEJIS, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, 2018.

Peña, A./Tubari, P./Chuve, L./Chore, M./Ipi, C. (2016). Historia de Lomerío. El camino hacia la libertad, in Inturias, M., Rodriguez, I./Valderomar, H./Peña, A. (eds) (2016). Justicia Ambiental y Autonomía Indígena de Base Territorial en Bolivia. Un dialogo político desde el Pueblo Monkox de Lomerío. University of East Anglia, Nur University, Grupo Confluencias and the Ministry of Autonomy, Bolivia.

Rodriguez, I./Inturias, M./Robledo, J./Sarti, C./Borel, R. (2019) La transformación de conflictos socio-ambientales. Un marco conceptual para la acción, in: Inturias, M./von Stosch, K./Balderomar, H./Rodriguez, I. (eds) (2019). Bolivia. Desafios socioambientales en las tierras bajas. Department of Investigative Social Science at Nur University, Bolivia. Available at: http://www.iics.nur.edu/publicaciones/editorial-nur/287-bolivia-desafios-socioambientales-en-las-tierras-bajas.

Rodríguez, I./Inturias, M. (2018). Conflict transformation in indigenous peoples’ territories: doing environmental justice with a ‘decolonial turn’, in: Development Studies Research, 5:1, 90-105, doi: 10.1080/21665095.2018.1486220.

Iokiñe and Mirna are activist-researchers, working since 2005 on transformative approaches for just and sustainable futures in indigenous peoples’ territories in Latina America. They have been working together since 2013 in Lomerio, Bolivia, helping to strengthen indigenous autonomy and the self-government of the Monkoxi indigenous peoples. Iokiñe works as a researchers and lecturer at the School of International Development (DEV) in the University of East Anglia, UK and Mirna as a researcher at Universidad NUR, Bolivia.